Wandering around Rome and dropping into churches where you can find extraordinary artworks, got me to thinking I should track down every Caravaggio in Rome. Doubtless been done numerous times before, but here is my attempt, together with a little bit of history about each painting.

Click on the gallery to go to the detail on each:

The National Gallery of Art - Palazzo Barberini

1. Judith Beheading Holofernes

2. Saint Francis in Meditation

3. Narcissus

4. Saint Francis in Prayer

The National Gallery of Art - Palazzo Corsini

5. John the Baptist

6. Penitent Magdalene

7. Rest on the Flight into Egypt

8. John the Baptist

9. Still Life with Fruit on a Stone

10. Boy with a Basket of Fruit

11. Young Sick Bacchus

12. Still Life with Flowers and Fruits

13. Saint Jerome Writing

14. The Madonna and Child with St Anne

15. David with the Head of Goliath

16. John The Baptist

17. The Fortune Teller

18. John the Baptist

19. The Calling of St Matthew

20. The Martyrdom of St Matthew

21. The Inspiration of St Matthew

22. Conversion of St Paul on the Road to Damascus

23. Crucifixion of Saint Peter

24. Entombment

25. Madonna of Loreto

26. Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto - ceiling fresco,

Villa Aurora.

27. Conversion of Saint Paul - Odescalchi Balbi

private collection

28. Portrait of Pope Paul V - Private Collection of

the Prince Borghese

29. Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy - Private Collection

The Palazzo Barberini, also known as The National Gallery of Art - Barberini. ![]()

Four Caravaggios in one of the biggest galleries in Rome

Let’s start with one of his best known paintings and undoubtedly my favourite ... and the most fabulously gruesome work.

1. Judith Beheading Holofernes 1599-1602

Judith saved her people by seducing and killing Holofernes, the Assyrian general. Judith gets Holofernes drunk, then seizes his sword and decapitates him. Judith embodies the power of the people of Israel to defeat the enemy, though superior in numbers, by means of cunning and courage.

Judith saved her people by seducing and killing Holofernes, the Assyrian general. Judith gets Holofernes drunk, then seizes his sword and decapitates him. Judith embodies the power of the people of Israel to defeat the enemy, though superior in numbers, by means of cunning and courage.

Caravaggio's approach was, typically, to choose the moment of greatest dramatic impact, the moment of the decapitation itself. The figures are set out in a shallow stage, theatrically lit from the side, isolated against the inky, black background. Judith and her maid Abra stand to the right, partially over Holofernes, who is vulnerable on his back.

The faces of the three characters demonstrate his mastery of emotion, Judith in particular showing in her face a mix of determination and repulsion.

The model for Judith is probably the Roman courtesan Fillide Melandroni, who posed for several other works by Caravaggio around this time. The scene itself and especially the details of blood and decapitation, were perhaps drawn from his observations of the public execution of Beatrice Cenci a few years before.

2. Saint Francis in Meditation

This is one of two paintings of almost identical paintings showing Saint Francis of Assisi contemplating a skull (the other is 'Saint Francis in Prayer') - neither is documented and both are disputed, although the dispute is as to whether they are originals or copies. The dating of both is highly uncertain, although the cypress trunk behind this Saint Francis is very reminiscent of the tree behind the Corsini 'John the Baptist'. St Francis was a popular subject during the Counter-Reformation, when the Church stressed - at least officially - the virtues of poverty and the imitation of Christ.

This is one of two paintings of almost identical paintings showing Saint Francis of Assisi contemplating a skull (the other is 'Saint Francis in Prayer') - neither is documented and both are disputed, although the dispute is as to whether they are originals or copies. The dating of both is highly uncertain, although the cypress trunk behind this Saint Francis is very reminiscent of the tree behind the Corsini 'John the Baptist'. St Francis was a popular subject during the Counter-Reformation, when the Church stressed - at least officially - the virtues of poverty and the imitation of Christ.

3. Narcissus 1599

This is one of only two known Caravaggios on a theme from Classical mythology, although this reflects the accidents of survival rather than the historical reality. The story of Narcissus, told by the poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses, is of a handsome youth who falls in love with his own reflection. Unable to tear himself away, he dies of his passion and even when crossing the Styx, keeps looking at his own reflection.

The story was well known in the circles of collectors, such as Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte and the banker Vincenzo Giustiniani, in which Caravaggio was moving at this period.

The story of Narcissus was particularly appealing to artists (or at least the kind who painted for the educated tastes of patrons such as Giustiniani and Del Monte), for reasons explained by the Renaissance theorist Leon Battista Alberti: "the inventor of painting ... was Narcissus ... What is painting but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool?"

Caravaggio painted an adolescent page wearing an elegant brocade doublet, leaning with both hands over the water, as he gazes at this own distorted reflection. The painting conveys an air of brooding melancholy: the figure of Narcissus is locked in a circle with his reflection, surrounded by darkness, so that the only reality is inside this self-regarding loop.

Caravaggio painted an adolescent page wearing an elegant brocade doublet, leaning with both hands over the water, as he gazes at this own distorted reflection. The painting conveys an air of brooding melancholy: the figure of Narcissus is locked in a circle with his reflection, surrounded by darkness, so that the only reality is inside this self-regarding loop.

The 16th.C. literary critic Tommaso Stigliani explained the contemporary thinking that the myth of Narcissus "clearly demonstrates the unhappy end of those who love their things too much."

4. Saint Francis in Prayer 1606

[on loan from San Pietro in Carpineto Romano]

This painting is unrecorded and therefore difficult to date, or even to distinguish the original from later copies.

St. Francis's life of poverty and humility was a popular subject in Caravaggio's age. St Francis of Assisi, together with John the Baptist and St Jerome, make up the trio of alienated males, young, mature and old, brooding and remote from human society, that Caravaggio painted again and again, becoming, in effect, private icons for Caravaggio’s own troubled life.

In the course of a libel trial in 1603, Caravaggio’s friend Orazio Gentileschi stated that he had lent the artist a monk's robe several months before, and this painting could be connected. Gentileschi’s evidence seems to be the main argument behind a 1602/1604 date. However others, on the grounds of the austere approach and less painterly technique of the work, believe that it may date from 1606, when Caravaggio had fled Rome as an outlaw following a death in a street brawl.

The National Gallery of Art - Corsini (in Trastevere) ![]()

5. John the Baptist 1604

This is one of two 'John the Baptists' painted by Caravaggio in or around 1604 (possibly 1605).

This is one of two 'John the Baptists' painted by Caravaggio in or around 1604 (possibly 1605).

The figure has been stripped of identifying symbols - no belt, not even the "raiment of camel's hair" and the reed cross is only suggested. The background and surrounds have darkened even further and there is the sense of a story from which the viewer is excluded.

Caravaggio was not the first artist to have treated the Baptist as a cryptic male nude - there were prior examples from Leonardo, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto and others - but he introduced a new note of realism and drama. His John has the roughened, sunburnt hands and neck of a labourer, his pale torso emerging with a contrast that reminds the viewer that this is a real boy who has gotten undressed for his modeling session - unlike Raphael's Baptist, who is as idealised and un-individualised as one of his winged cherubs.

The unknown model actually is a record of Rome itself in the age of Caravaggio. Biographer Peter Robb cites Montaigne on Rome as a city of universal idleness, "...the envied idleness of the higher clerics, and the frightening idleness of the destitute...a city almost without trades or professions, in which the churchmen were playboys or bureaucrats, the laymen were condemned to be courtiers, all the pretty girls and boys seemed to be prostitutes, and all wealth was inherited old money or extorted new."

It was not an age which welcomed an art that emphasised the real.

6. Penitent Magdalene 1595

The painting depicts a young brunette, kneeling on a low chair, with her hands cradled in her lap. By her side is a collection of jewelry and a stoppered bottle of liquid, nearly three-quarters full. Her gaze is averted from the viewer, her head turned downward in a position that has been compared to traditional portrayals of the crucified Jesus Christ. A single tear runs down one cheek to the side of her nose.

The painting was completed ca. 1594-1595. Caravaggio was known to have used several prostitutes as models for his works and historians have speculated that Anna Bianchini is featured in this painting. Contemporary biographers indicate Bianchini may also have featured in Caravaggio's Death of the Virgin, Conversion of the Magdalen (as Martha) and Rest on the Flight into Egypt (as the Virgin Mary). It may be the first religious painting ever completed by Caravaggio.

This painting represents a departure from the standard paintings of the penitent Mary Magdalene of Caravaggio's day in portraying her in contemporary clothing. Indeed most of the many depictions of the subject in art showed the Magdalen with no clothing at all, it having fallen apart during the thirty years she spent, according to medieval legend, repenting in the desert after the Ascension of Jesus. It was Caravaggio's departure into realism that shocked the audience.

7. Rest on the Flight into Egypt 1594

The scene is based not on any incident in the Bible itself, but on a body of tales or legends that had grown up in the early Middle Ages around the Bible story of the Holy Family fleeing into Egypt for refuge on being warned that Herod the Great was seeking to kill the Christ Child. According to the legend, Joseph and Mary paused on the flight in a grove of trees; the Holy Child ordered the trees to bend down so that Joseph could take fruit from them, and then ordered a spring of water to gush forth from the roots so that his parents could quench their thirst. This basic story acquired many extra details during the centuries.

Caravaggio shows Mary asleep with the infant Jesus, while Joseph holds a manuscript for an angel who is playing a hymn to Mary on the violin.

The date of the painting is disputed but probably 1594. This was the first large-scale work done by Caravaggio and is compositionally more ambitious and more successful earlier works. It is also one of the very rare landscapes from this artist who seems always to have been painting in a prison cell, a room at a tavern, or at night - one critic has joked that all the sky in all Caravaggio's 80-odd works would add up to a few square centimeters of paint.

The painting was apparently sold to the Pamphilj by the early 17th century. Caravaggio's Lombard and Venetian heritage are evident in the treatment of the landscape and in the luminous tones. Like most depictions of the flight to Egypt, this is a peaceful moment, one in which the scenery is to be enjoyed, more gardenscape than landscape. The luminous figure of the adolescent angel, at once serene and sensuous, holds the centre of the group. The mother and child grouping, one of many that Caravaggio would paint, is comparable in its delicacy and realism to the best that the thousands in the canon can offer.

One of the great pastimes of Caravaggio scholars is identifying his models. Caravaggio left few clues. Mary appears to be the same girl who appears as Mary Magdalen in The Penitent Magdalene of about 1597, also in the Doria-Pamphilj Gallery. The aged Joseph appears similar to the elderly saints in The Inspiration of Saint Matthew of 1602 and, less clearly, Saint Jerome in Meditation of about 1605. Some critics have identified the boy-angel with the ingenuous victim of cheats on the left of Cardsharps, while others have seen a similarity with the boy cheating him instead.

8. John the Baptist 1601

The youthful John is shown half-reclining, one arm around a ram's neck, his turned to the viewer with an impish grin. There's almost nothing to signify that this indeed the prophet sent to make straight the road in the wilderness – no cross, no leather belt, just a scrap of camel's skin lost in the voluminous folds of the red cloak, and the ram. The ram itself is highly un-canonical – John the Baptist's animal is supposed to be a lamb, marking his greeting of Christ as the 'Lamb of God, come to take away the sins of mankind'. The ram is as often a symbol of lust as of sacrifice, and this naked smirking boy conveys no sense of sin whatsoever.

This painting proved immensely popular - eleven known copies were made, including this one recognised by scholars as being from Caravaggio's own hand. Another is in the Gallery Borghese. The collectors ordering the copies would have been aware of a further level of irony: the pose adopted by the model is a clear imitation of that adopted by one of Michelangelo's famous ignudi on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The role of these gigantic male nudes in Michelangelo's depiction of the world before the Laws of Moses has always been unclear - some have supposed them to be angels, others that they represent the ideal of human beauty - but for Caravaggio to pose his adolescent assistant as one of the Master's dignified witnesses to the Creation was clearly a kind of in-joke for the cognoscenti.

1601/02 was one of the most productive periods in a productive career. Caravaggio was apparently living and painting in the palazzo of the Mattei family, inundated with commissions from wealthy private clients following the success of the Contarelli chapel where in 1600 he had displayed 'The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew' and 'The Inspiration of Saint Matthew'. But for all this success, the Church itself had not yet commissioned anything. The paintings in the Contarelli Chapel had been commissioned and paid for by private patrons, although the priests of San Luigi dei Francesi (which contains the chapel) had had to approve the result. Caravaggio's problem was that the Counter-Reformation Church was extremely conservative - there had been a move to introduce an Index of Prohibited Images, and high-ranking cardinals had published handbooks guiding artists, and more especially the priests who might commission artists or approve art, on what was and was not acceptable. And the playful crypto-paganism of this private 'John the Baptist' with its cross-references to the out of favour 'classicising humanism' of Michelangelo and the High Renaissance, most certainly was not acceptable.

9. Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge c.1601

Variously dated between 1601 and 1605. It depicts a wicker basket heaped with various fruit and vegetables sitting on a stone table, caught in Caravaggio's usual strong yet mellow shaft of light falling from top left, "as if through a hole in the ceiling." (Caravaggio at around this time was sued by a landlady for having cut a hole in the ceiling of the rooms he rented, presumably to create his characteristic lighting).

Variously dated between 1601 and 1605. It depicts a wicker basket heaped with various fruit and vegetables sitting on a stone table, caught in Caravaggio's usual strong yet mellow shaft of light falling from top left, "as if through a hole in the ceiling." (Caravaggio at around this time was sued by a landlady for having cut a hole in the ceiling of the rooms he rented, presumably to create his characteristic lighting).

While at one level the painting is a bravura study of texture and form and light, the Renaissance symbology of fruit and vegetables was rich and intricate, and given this fact and the fact that so many of Caravaggio's apparently simple paintings, such as 'Boy Bitten by a Lizard', in fact carry coded messages, it is not unlikely that the 'Still Life with Fruit' is equally complex. Nevertheless, no plausible reading has so far been advanced, although several commentators have noted the visual suggestiveness of the moistly cut fruits and melons and the writhing, thrusting marrows.

10. Boy with a Basket of Fruit c.1593

This painting dates from the time when Caravaggio, newly arrived in Rome from his native Milan, was making his way in the competitive Roman art world. The model was his friend and companion, the Sicilian painter Mario Minniti, at about 16 years old.

This painting dates from the time when Caravaggio, newly arrived in Rome from his native Milan, was making his way in the competitive Roman art world. The model was his friend and companion, the Sicilian painter Mario Minniti, at about 16 years old.

The work was in the collection of Giuseppe Cesari, the Cavaliere d'Arpino, seized by Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1607, but it may date from a slightly later period when Caravaggio and Minniti had left Cavalier d'Arpino's workshop (January 1594) to make their own way selling paintings through the dealer Costantino. Certainly it cannot predate 1593, the year Minniti arrived in Rome.

It is believed to predate more complex works from the same period (also featuring Minniti as a model) such as 'The Fortune Teller' and 'The Cardsharps' (both 1594), the latter of which brought Caravaggio to the attention of his first important patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte.

At one level the painting is a genre piece designed to demonstrate the artist's ability to depict everything from the skin of the boy to the skin of a peach, from the folds of the robe to the weave of the basket.

11. Young Sick Bacchus also known as

The Sick Bacchus or the Self-Portrait as Bacchus 1593 - 1594

According to Caravaggio's first biographer, Giovanni Baglione, this is a cabinet piece painted by the artist using a mirror. The painting dates from Caravaggio's first years in Rome following his arrival from his native Milan in mid-1592. Sources for this period are inconclusive and probably inaccurate, but they agree that at one point the artist fell extremely ill and spent six months in the hospital of Santa Maria della Consolazione. The painting indicates that Caravaggio's physical ailment likely involved malaria, as the jaundiced appearance of the skin and the icterus in the eyes are indications of some active hepatic disease causing high levels of bilirubin.

According to Caravaggio's first biographer, Giovanni Baglione, this is a cabinet piece painted by the artist using a mirror. The painting dates from Caravaggio's first years in Rome following his arrival from his native Milan in mid-1592. Sources for this period are inconclusive and probably inaccurate, but they agree that at one point the artist fell extremely ill and spent six months in the hospital of Santa Maria della Consolazione. The painting indicates that Caravaggio's physical ailment likely involved malaria, as the jaundiced appearance of the skin and the icterus in the eyes are indications of some active hepatic disease causing high levels of bilirubin.

'The Sick Bacchus' was among the many works making up the collection of Giuseppe Cesari, one of Caravaggio's early employers, which was seized by the art-collector Cardinal-Nephew Scipione Borghese in 1607, together with the 'Boy Peeling Fruit' and 'Boy with a Basket of Fruit'.

Apart from its assumed autobiographical content, this early painting was likely used by Caravaggio to market himself, demonstrating his virtuosity in painting genres such as still-life and portraits and hinting at the ability to paint the classical figures of antiquity. The three-quarters angle of the face was among those preferred for late renaissance portraiture, but what is striking is the grimace and tilt of the head, and the very real sense of the suffering; a feature that most Baroque art shares. The still-life can be compared with that contained in slightly later works such as the 'Boy With a Basket of Fruit' and the 'Boy Bitten by a Lizard' where the fruits are in a much better condition, reflecting no doubt Caravaggio's improved condition, both physically and mentally.

12. Still Life with Flowers and Fruits

According to tradition, Caravaggio painted flowers and fruit when he first came to Rome. Individual pieces of this 'Still Life with Flowers and Fruit' are brilliantly painted and call to mind the mastery of such subjects that Caravaggio showed in early works such as 'Boy with a Basket of Fruit', as well as his reported comment that it took as much trouble to paint a flower as it did to paint a man. Nevertheless, the overall composition is awkward and it is not accepted by all as genuine.

According to tradition, Caravaggio painted flowers and fruit when he first came to Rome. Individual pieces of this 'Still Life with Flowers and Fruit' are brilliantly painted and call to mind the mastery of such subjects that Caravaggio showed in early works such as 'Boy with a Basket of Fruit', as well as his reported comment that it took as much trouble to paint a flower as it did to paint a man. Nevertheless, the overall composition is awkward and it is not accepted by all as genuine.

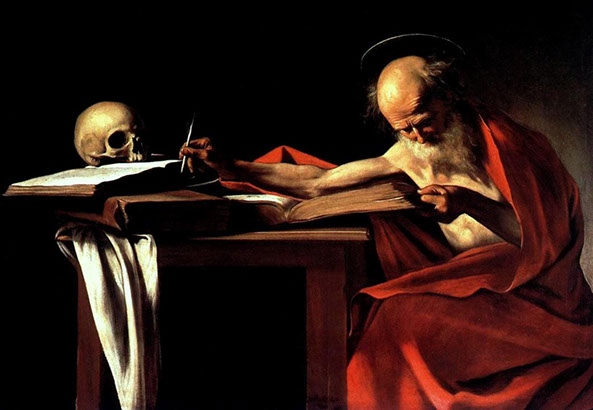

13. Saint Jerome Writing also called Saint Jerome in His Study 1605-1606

The painting depicts Saint Jerome, a Doctor of the Church in Roman Catholicism and a popular subject for painting, even for Caravaggio, who produced other paintings of Jerome in Meditation and engaged in writing. In this image, Jerome is reading intently, an outstretched arm resting with quill. It has been suggested that Jerome is depicted in the act of translating the Vulgate.

The painting depicts Saint Jerome, a Doctor of the Church in Roman Catholicism and a popular subject for painting, even for Caravaggio, who produced other paintings of Jerome in Meditation and engaged in writing. In this image, Jerome is reading intently, an outstretched arm resting with quill. It has been suggested that Jerome is depicted in the act of translating the Vulgate.

Caravaggio produced the piece at the behest of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, who became a cardinal in 1605, but it is possible that Borghese acquired it later as it is not mentioned in a 1613 poem by Scipione Francucci that described the Borghese Caravaggio collection. Whether or not the dating is accurate, the work is believed to have originated from Caravaggio's late Roman period, which ended with the painter's exile to Malta in 1606.

That Saint Jerome Writing is the work of Caravaggio is sometimes brought into question, as it was attributed to Ribera in the

Borghese inventories from 1700 until 1893.

14. The Madonna and Child with St. Anne 1605-1606

Painted for the altar of Archconfraternity of the Papal Grooms in the Basilica of Saint Peter. The painting was briefly exhibited in the parish church for the Vatican, the church of Sant'Anna dei Palafrenieri on the Via di Porta Angelica in Borgo, near the Vatican. It was subsequently sold to Cardinal Borghese.

Painted for the altar of Archconfraternity of the Papal Grooms in the Basilica of Saint Peter. The painting was briefly exhibited in the parish church for the Vatican, the church of Sant'Anna dei Palafrenieri on the Via di Porta Angelica in Borgo, near the Vatican. It was subsequently sold to Cardinal Borghese.

While not his most successful arrangement, it is an atypical representation of the Virgin for its time and must have been shocking to some contemporary viewers. The allegory, at its core, is simple. The Virgin, with the aid of her son, whom she holds, tramples on a serpent, the emblem of evil or original sin. Saint Anne, whom the painting is intended to honor, is a wrinkled old grandmother, witnessing the event. Flimsy halos crown the upright; the snake recoils in anti-halos. Both Mary and Jesus are barefoot; Jesus is a fully naked uncircumcised child. All else is mainly shadow and the figures gain monumentality in the light.

If this painting was meant to honor the grandmother of Christ, it is unclear how the ungracious depiction of her wrinkled visage in this painting would have been seen as reverent or iconic. Further shock must have accrued at the Virgin Mary’s revealing bodice. One could speculate that the parallel diagonals of Jesus’ phallus and leg suggest that both battle the snake.

15. David with the Head of Goliath 1605

The painting, which was in the collection of Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1650, has been dated as early as 1605 and as late as 1609 –1610, with more recent scholars tending towards the former.

The painting, which was in the collection of Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1650, has been dated as early as 1605 and as late as 1609 –1610, with more recent scholars tending towards the former.

The immediate inspiration for Caravaggio is a work by a follower of Giorgione, c.1510, but Caravaggio captures the drama more effectively by having the head dangling from David's hand and dripping blood, rather than resting on a ledge. The sword in David's hand carries an abbreviated inscription

H-AS OS; this has been interpreted as an abbreviation of the Latin phrase Humilitas occidit superbiam ("humility kills pride").

David is perturbed, his expression mingling sadness and compassion. The decision to depict him as pensive rather than jubilant creates an unusual psychological bond between him and Goliath. This bond is further complicated by the fact that Caravaggio has depicted himself as Goliath, while the model for David is 'il suo Caravaggino' ("his own little Caravaggio"). This most plausibly refers to Cecco del Caravaggio, the artist's studio assistant in Rome some years previously, recorded as the boy "who lay with him." No independent portraits of Cecco are known, making the identification impossible to verify, but "[a] sexual intimacy between David/model and Goliath/painter seems an inescapable conclusion, however, given that Caravaggio made David's sword appear to project upward, suggestively, between his legs and at an angle that echoes the diagonal linking of the protagonist's gaze to his victim." In the alternative and based on the portrait of Caravaggio done by Ottavio Leoni, it appears that this, the Borghese version of 'David with the Head of Goliath', may be a double self-portrait. The young Caravaggio (his own little Caravaggio) wistfully holds the head of the adult Caravaggio. The wild and riotous behavior of the young Caravaggio essentially had destroyed his life as a mature adult and he reflects with a familiar hermeticism on his own condition in a painting of a not entirely unrelated religious subject.

The biographical interest of the painting adds another layer of meaning to an already complex work, David and Goliath standing for Christ and Satan and the triumph of good over evil in orthodox Christian iconography of the period and also as the cold-hearted beloved who "kills" and his lover according to contemporary literary conceit, although Caravaggio has depicted David not as cruel and indifferent but as deeply moved by Goliath's death.

If the painting was a gift to Cardinal Borghese, the papal official with the power to grant Caravaggio a pardon for murder, it can also be interpreted as a personal plea for mercy. 'David with the Head of Goliath' demonstrates Caravaggio's gift for distilling his own experiences into an original sacred imagery that transcends the personal to become a searing statement of the human condition.

16. John the Baptist 1610

The painting shows a boy slumped against a dark background, where a sheep nibbles at a dull brown vine. The boy is immersed in a reverie: perhaps as Saint John he is lost in private melancholy, contemplating the coming sacrifice of Christ; or perhaps as a real-life street-kid called on to model for hours he is merely bored. As so often with Caravaggio, the sense is of both at once. But the overwhelming feeling is of sorrow. The red cloak envelopes his puny childish body like a flame in the dark, the sole touch of colour apart from the pale flesh of the juvenile saint.

Cardinal Borghese was a discriminating collector but notorious for extorting and even stealing pieces that caught his eye - he, or rather his uncle Pope Paul V, had recently imprisoned Giuseppe Cesari, one of the best-known and most successful painters in Rome, on trumped-up charges in order to confiscate his collection of one hundred and six paintings.

By 1610 Caravaggio's life was unraveling. In 1606 he had fled Rome as an outlaw after killing a man in a street fight; in 1608 he had been thrown into prison in Malta and again escaped; through 1609 he had been pursued across Sicily by his enemies until taking refuge in Naples, where he had been attacked in the street by unknown assailants within days of his arrival. Now he was under the protection of the Colonna family in the city, seeking a pardon that would allow him to return to Rome. The power to grant the pardon lay in the hands of the art-loving Cardinal Borghese, who would expect to be paid in paintings. News that the pardon was imminent arrived in mid-year and the artist set out by boat with three canvasses. The next news was that he had died "of a fever" in Porto Ercole, a coastal town north of Rome held by Spain.

17. The Fortune Teller 1594

Here we have a foppishly-dressed boy having his palm read by a gypsy girl. The boy looks pleased as he gazes into her face, and she returns his gaze. Close inspection of the painting reveals what the young man has failed to notice: the girl is removing his ring as she gently strokes his hand.

Here we have a foppishly-dressed boy having his palm read by a gypsy girl. The boy looks pleased as he gazes into her face, and she returns his gaze. Close inspection of the painting reveals what the young man has failed to notice: the girl is removing his ring as she gently strokes his hand.

Caravaggio picked the gypsy girl out from passers-by on the street and used her as his model in order to demonstrate that he had no need to copy the works of the masters from antiquity. He is said to have pointed towards a crowd of people saying that “nature had given him an abundance of masters."

This story is often used to demonstrate that the classically trained Mannerist artists of Caravaggio's day disapproved of Caravaggio's insistence on painting from life instead of from copies and drawings made from older masterpieces.

In acknowledgment, it was also said at the time that “in these two half-figures Caravaggio translated reality so purely that it came to confirm what he said." The story is probably apocryphal but it does indicate the essence of Caravaggio's revolutionary impact on his contemporaries - beginning with 'The Fortune Teller' - which was to replace the Renaissance theory of art as a fiction with art as the representation of real life.

The 1594 'Fortune Teller' aroused considerable interest among younger artists and the more avant garde collectors of Rome, but Caravaggio's poverty forced him to sell it for the low sum of eight scudi. It entered the collection of a wealthy banker and connoisseur, the Marchese Vincente Giustiniani, an important patron of the artist. Giustiniani's friend, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, purchased the companion piece, Cardsharps, in 1595, and at some point in that year Caravaggio entered the Cardinal's household.

One year later, Caravaggio painted a second version of 'The Fortune Teller', for Maria Del Monte, copied from the original but with some minor changes. This now hangs in The Louvre.

18. John the Baptist 1602

Painted in 1602, this is the original, from which several copies were made, some verified as being by Caravaggio himself.

Painted in 1602, this is the original, from which several copies were made, some verified as being by Caravaggio himself.

A full description is with No. 8 on this list at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj (a Caravaggio copy).

Contarelli Chapel - Church of San Luigi die Francesi ![]()

At last!... three free Caravaggios, all to be found in the “French Church” just near the Pantheon.

19. The Calling of Saint Matthew 1600

The painting tells the story from the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 9:9): "Jesus saw a man named Matthew at his seat in the custom house, and said to him, "Follow me", and Matthew rose and followed Him."

The painting tells the story from the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 9:9): "Jesus saw a man named Matthew at his seat in the custom house, and said to him, "Follow me", and Matthew rose and followed Him."

Caravaggio depicts Matthew as a tax collector sitting at a table with four other men. Jesus and St Peter have entered the room and Jesus is pointing at Matthew. A beam of light illuminates the faces of the men at the table who are looking at Jesus.

Over a decade before, Cardinal Matteo Contarelli had left in his will funds and specific instructions for the decoration of a chapel based on themes related to his namesake, St Matthew. The dome of the chapel was decorated with frescoes by the late Mannerist artist Cavalier D'Arpino, Caravaggio's former employer and one of the most popular painters in Rome at the time. But as D'Arpino became busy with royal and papal patronage, Cardinal Francesco Del Monte, Caravaggio's patron, intervened to obtain for Caravaggio his first major church commission and his first painting with more than a handful of figures.

The Calling hangs opposite 'The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew'. (below). While the Martyrdom was probably the first to be started, the Calling was the first to be completed. The commission for these two paintings is dated July 1599 with final payment made in July 1600. Between the two, at the altar, is 'The Inspiration of Saint Matthew'. (below).

There is some debate over which man in the picture is Saint Matthew, as the surprised gesture of the bearded man at the table can be read in two ways. Most writers on 'The Calling' assume Saint Matthew to be the bearded man, and see him to be pointing at himself, as if to ask "Me?" in response to Christ's summons. This theory is strengthened when one takes into consideration the other two works in this series, 'The Inspiration of Saint Matthew', and the 'The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew'. The bearded man who models as Saint Matthew appears in all three works, with him unequivocally playing the role of Saint Matthew in both the Inspiration and the Martyrdom.

A recent interpretation has the bearded man in fact pointing at the young man at the end of the table, whose head is slumped. In this reading, the bearded man is asking "Him?" in response to Christ's summons and the painting is depicting the moment immediately before a young Matthew raises his head to see Christ. Other writers describe the painting as deliberately ambiguous.

20. The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew 1602

See also notes on No 19, above.

According to tradition, Saint Matthew was killed on the orders of the King of Ethiopia while celebrating Mass at the altar. The king lusted after his own niece and had been rebuked by Matthew as the girl was a nun and therefore the bride of Christ. Cardinal Contarelli, who had died several decades earlier, had laid down very explicitly what was to be shown: the saint being murdered by a soldier sent by the wicked king, some suitable architecture, and crowds of onlookers showing appropriate emotion.

According to tradition, Saint Matthew was killed on the orders of the King of Ethiopia while celebrating Mass at the altar. The king lusted after his own niece and had been rebuked by Matthew as the girl was a nun and therefore the bride of Christ. Cardinal Contarelli, who had died several decades earlier, had laid down very explicitly what was to be shown: the saint being murdered by a soldier sent by the wicked king, some suitable architecture, and crowds of onlookers showing appropriate emotion.

The commission caused Caravaggio considerable difficulty, as he had never painted so large a canvas, nor one with so many figures. X-rays reveal two separate attempts, with a general movement towards simplification through reduction in the number of figures and reduction – ultimately elimination – of the architectural element.

The version we see today has the action caught at the moment of highest drama, the bystanders reduced to supporting roles by the sharply selective light, the whole giving the impression of a moment seen as if in a lightning flash.

This painting marks the moment when the Mannerist orthodoxy of the late 16th century – rational, intellectual, perhaps a little artificial – gives way to the Baroque. It caused a sensation. Federico Zuccari, one of the most eminent painters in Rome and a champion of Mannerism, came to see, and sniffed that it was nothing. But the younger artists were totally won over and Caravaggio became suddenly the most famous artist in Rome.

21. The Inspiration of Saint Matthew 1602

See also notes on 'The Calling of St Matthew', above.

See also notes on 'The Calling of St Matthew', above.

All is darkness but for the two figures, with St Matthew appearing to have rushed to his desk, anxious to begin his work. Encouraged by the angel, his stool teetering as he kneels.

Caravaggio’s patron, the Cardinal del Monte, commissioned this work in 1602, but rejected the first two versions. One of these was destroyed in WWII, the other painted over. The first versions had the angel standing with St Matthew.

In the final (above), the angel directly offers inspiration to the restless St Matthew. The angel adopts a sublime suspension, enveloped in an encircling sheet.

The original painting, rejected by Cardinal

The original painting, rejected by Cardinal

del Monte.

Destroyed in the bombing of Dresden

in WWII.

Ceresi Chapel - Santa Maria del Popolo ![]()

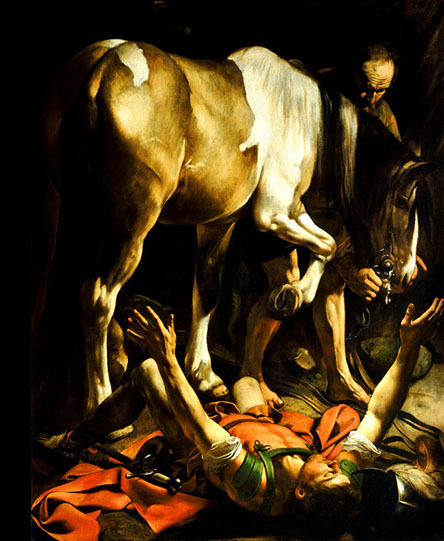

22. The Conversion of St Paul 1600

The painting depicts the moment recounted in Chapter 9 of Acts of the Apostles when Saul, soon to be the apostle Paul, fell on the road to Damascus. He heard the Lord say "I am Jesus, whom you persecute, arise and go into the city" (see 'Conversion of Paul'). The Golden Legend, a compilation of medieval interpretations of biblical events, may have framed the event for Caravaggio. 'The Conversion of St. Paul' depicts a moment of intense religious ecstasy. This scene shows the very moment Paul is overcome with the spirit of Jesus Christ and has been flung off of his horse.

The painting depicts the moment recounted in Chapter 9 of Acts of the Apostles when Saul, soon to be the apostle Paul, fell on the road to Damascus. He heard the Lord say "I am Jesus, whom you persecute, arise and go into the city" (see 'Conversion of Paul'). The Golden Legend, a compilation of medieval interpretations of biblical events, may have framed the event for Caravaggio. 'The Conversion of St. Paul' depicts a moment of intense religious ecstasy. This scene shows the very moment Paul is overcome with the spirit of Jesus Christ and has been flung off of his horse.

Caravaggio's first version of 'The Conversion' is in the collection of Principe Guido Odescalchi. It is a much brighter and more Mannerist canvas, with an angel-suspended Jesus reaching downwards towards a blinded Paul.

In 'The Conversion of St. Paul' Caravaggio focuses on St. Paul’s internal involvement with this moment of religious ecstasy, by creating a dark and mysterious background. Although the viewer does not see a heavenly apparition, the scene can be easily identified as St. Paul’s conversion because of the emotions, that are intensified by the lighting, shown by the apostle.

In this specific painting, Caravaggio uses not only dramatic lighting but the placement of the characters to intensify the moment of conversion. St. Paul, the main character, is flung off of his horse and is seen on his back, on the ground. Although Paul reflects the most light out of all the characters, the attention is given to him in a strange way. Because Paul is on the ground, he is much smaller than the horse, which is also at the center of the painting. Paul’s body is foreshortened, and is not facing the viewer, and yet his presence is the most powerful because of his body pushing into the viewer's space. Out the three characters in the painting - the horse, the groom, and Paul - Paul is the only one really pushing into the space of the viewer.

What is more interesting, is the aloof and unknowing postures of the groom and the horse. As Paul is on the ground with his arms thrown into the air, the groom and the horse don’t seem to notice. Along with this contrast of emotions, the leg and position of the horse creates even more visual tension. The horse, while taking up a lot of room on the painting, gives another layer of tension with the position of his front leg. Strangely pointed out towards the viewer, with the use of heavy foreshortening, this almost 3-D representation of the hoof shows more imbalance and tension.

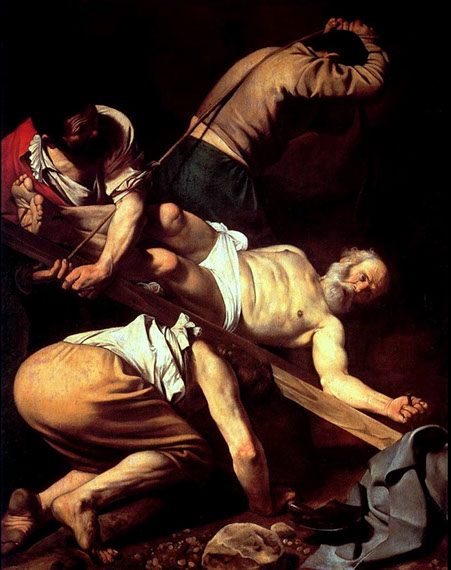

23. The Crucifixion of St Peter 1601

The painting depicts the martyrdom of St. Peter by crucifixion - Peter asked that his cross be inverted so as not to imitate his God, Jesus Christ, hence he is depicted upside down. The large canvas shows Ancient Romans, their faces shielded, struggling to erect the cross of the elderly but muscular apostle. Peter is heavier than his aged body would suggest, and his lifting requires the efforts of three men, as if the crime they perpetrate already weighs on them.

The painting depicts the martyrdom of St. Peter by crucifixion - Peter asked that his cross be inverted so as not to imitate his God, Jesus Christ, hence he is depicted upside down. The large canvas shows Ancient Romans, their faces shielded, struggling to erect the cross of the elderly but muscular apostle. Peter is heavier than his aged body would suggest, and his lifting requires the efforts of three men, as if the crime they perpetrate already weighs on them.

The two Caravaggios in the Ceresi Chapel, as well as the altarpiece by Carracci, were commissioned in September 1600 by Monsignor Tiberio Cerasi, who died shortly afterwards. Caravaggio's original versions of both paintings were rejected. They passed into the private collection of Cardinal Sannessio, and several modern scholars including John Gash, Helen Lagdon and Peter Robb, have speculated that Sennassio may have taken advantage of Cerasi's sudden death to seize some pictures by Rome's most famous new painter. The first Conversion of Paul has been identified with 'The Conversion of Saint Paul' in the Odescalchi Balbi Collection, Rome, but the first version of The Crucifixion of Peter has disappeared; some scholars have identified it with a painting now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, but this is not generally accepted (in the Hermitage catalog Martyrdom of St. Peter is attributed, with a question mark, to Lionello Spada and dated on the first quarter of the 17th century). In all events, the second versions, which seem to have been more unconventional than the first, were accepted without comment by the executors of Cerasi's estate in 1601.

The two saints, Peter and Paul, together represent the foundations of the Catholic Church, Peter the rock upon which Christ declared his Church to be built (Gospel of Matthew 16:18), and Paul who founded the seat of the church in Rome. Caravaggio's paintings were thus intended to symbolise Rome's (and Cerasi's) devotion to the Princes of the Apostles in this church which dominated the great piazza welcoming pilgrims as they entered the city from the north, representing the great Counter-Reformation themes of conversion and martyrdom and serving as propaganda against the twin threats of backsliding and Protestantism.

Caravaggio, or his patron, appear to have had in mind the Michelangelo frescoes in the Vatican's Capella Paolina when choosing the subjects for these paintings. However, the Caravaggio scene is far more stark than Michelangelo's confusing mannerist miracle in the Vatican.

24. Entombment 1603

Caravaggio created this, one of his most admired altarpieces, in 1603–1604 for the second chapel on the right in Santa Maria in Vallicella (the Chiesa Nuova), a church built for the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri. A copy of the painting is now in the chapel and the original is in the Vatican Museum.

Caravaggio created this, one of his most admired altarpieces, in 1603–1604 for the second chapel on the right in Santa Maria in Vallicella (the Chiesa Nuova), a church built for the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri. A copy of the painting is now in the chapel and the original is in the Vatican Museum.

The Entombment was probably planned and begun in 1602/3. The chapel in which it was to be hung, was dedicated to the Pietà and occupied a 'privileged' position in the Chiesa Nuova. Mass could be celebrated from it and it was granted special indulgences.

Some time after Niri’s death in March 1600, a legacy of 1,000 scudi became available for the maintenance of the chapel and it was built in 1602.

The painting was universally admired and written about by critics. The painting was taken to Paris in 1797 for the Musée Napoléon, returned to Rome and installed in the Vatican in 1816

This counter-reformation painting – with a diagonal cascade of mourners and cadaver-bearers descending to the limp, dead Christ and the bare stone – is not a moment of transfiguration, but of mourning. As the viewer's eye descends from the gloom there is, too, a descent from the hysteria of Mary of Clopas (wife of Clopas, a contemporary of Jesus and present at the crucifixion) through subdued emotion to death as the final emotional silencing. As opposed to the gory post-crucifixion Jesus’ in morbid Spanish paintings, Italian Christs die generally bloodlessly and slump in a geometrically challenging display. As if emphasising the dead Christ's inability to feel pain, a hand enters the wound at his side. His body is one of a muscled, veined, thick-limbed laborer rather than the usual, bony-thin depiction.

Two men carry the body. John the Evangelist, identified only by his youthful appearance and red cloak supports the dead Christ on his right knee and with his right arm, inadvertently opening the wound. Nicodemus grasps the knees in his arms, with his feet planted at the edge of the slab. Caravaggio balances the stable, dignified position of the body and the unstable exertions of the bearers.

While faces are important in painting generally, in Caravaggio it is important always to note where the arms are pointing. Here, the dead Jesus’ fallen arm and immaculate shroud touch stone; the grieving Mary gesticulates to Heaven, a parallel to the message of Christ: God come to earth, and mankind reconciled with the heavens. As usual, even with his works of highest devotion, Caravaggio never fails to ground himself. In the center is Mary Magdalene, drying her tears with a white handkerchief, face shadowed. Tradition held that the Virgin Mary be depicted as eternally young, but here Caravaggio paints the Virgin as an old woman. The figure of the Virgin Mary is also partially obscured behind John; we see her in the robes of a nun and her arms are held out to her side, imitating the line of the stone they stand upon. Her right hand hovers above his head as if she is reaching out to touch him. Seen together, the three women constitute different, complementary expressions of suffering.

Although Caravaggio's 'Entombment of Christ' is related to Michelangelo's Pieta, it is not a Pieta because even if there is the presence of the Virgin Mary in the painting there are not the right number nor types of people present. 'Entombment of Christ' is also not a Burial because the body of Christ is not being lowered on to a tomb but instead being laid on a stone slab. The composition assumes the traditional pyramidal shape of a traditional Pietà type. The flat stone (previously interpreted as a lid or door to a tomb) can be reinterpreted as a reference to the Stone of Unction, today enshrined in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. This stone was used to place Christ's body when it was anointed and wound in linen clothes, as related in the Gospel of John.

Seldom noticed by modern viewers is Caravaggio's insertion of the plant in the lower left. Commonly called mullein, Verbascum thapsus was thought to have medicinal properties and was said to ward off evil spirits. It was associated with the iconography of Saint John the Baptist. Caravaggio also uses it in his 'Saint John the Baptist' and 'Rest on the Flight into Egypt'.

Caravaggio's painting is a visual counterpart to the Mass, with the priest raising the newly consecrated host with the Entombment as a backdrop. The privileged placement of the altar would have meant that this was a daily occurrence; the act perfectly juxtaposing the body in the picture with the host as the priest intones "This is my very body."

Cavalletti Chapel - Church of Saint Agostino ![]()

25. Madonna of Loreto 1603

This depicts the apparition of the barefoot Virgin and naked child to two peasants on a pilgrimage, or as some say it is the coming to life of the iconic statue of the Virgin.

This depicts the apparition of the barefoot Virgin and naked child to two peasants on a pilgrimage, or as some say it is the coming to life of the iconic statue of the Virgin.

In 1603 the heirs of marquis Ermete Cavalletti, who had died on 21 July 1602, commissioned a painting on the theme of the Madonna of Loreto for decoration of a family chapel in the church of Sant' Agostino, near the Piazza Navona.

Giovanni Baglione, a competing painter of lesser talent, but who had successfully obtained Caravaggio's jailing during a libel trial, said that the unveiling of this painting "caused the common people to make a great cackle (schiamazzo) over it". The uproar was not surprising. The Virgin Mary, like her admiring pilgrims, is barefoot. The doorway or niche is not an exalted cumulus or bevy of putti, but a partly decrepit wall of flaking brick is visible. Only the merest halo sanctifies her and the baby. While beautiful, the Virgin Mary could be any woman, emerging from the night shadows.

Like many of Caravaggio's Roman paintings, such as the 'Conversion on the Way to Damascus' or the 'Calling of St Matthew', the scene is a moment where an everyday common person encounters the divine, whose appearance is also not unlike that of a commoner. The woman modelling Mary appears to be the same as that in the canvas in the 'The Madonna and Child with St. Anne' (No. 14 in this list) in the Galleria Borghese.

Villa Aurora - private collection ![]()

26. Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto … ceiling painting

Located in the Villa Aurora, the former hunting lodge of the Villa Ludovisi, Rome. It is unusually painted in oils on plaster and hence it is not a fresco, although it is sometimes (incorrectly) referred to as such. Oil painting is normally on canvas or less frequently, on wood.

Located in the Villa Aurora, the former hunting lodge of the Villa Ludovisi, Rome. It is unusually painted in oils on plaster and hence it is not a fresco, although it is sometimes (incorrectly) referred to as such. Oil painting is normally on canvas or less frequently, on wood.

According to an early biographer, one of Caravaggio's aims was to discredit critics who claimed that he had no grasp of perspective. The three figures demonstrate the most dramatic foreshortening imaginable. They contradict claims that Caravaggio always painted from live models. The artist seems to have used his own face for all three gods, as well, it is rumoured, his own genitalia.

The painting was done for Caravaggio's patron Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte and painted on the ceiling of the cardinal's garden casino of his country estate, which later became known as the Villa Ludovisi. The cardinal had a keen interest alchemy. Caravaggio has painted an allegory of the alchemical triad of Paracelsus: Jupiter stands for sulphur and air, Neptune for mercury and water, and Pluto for salt and earth. Each figure is identified by his beast: Jupiter by the eagle, Neptune by the hippocamp, and Pluto by the three-headed dog Cerberus. Jupiter is reaching out to move the celestial sphere in which the Sun revolves around the Earth. Galileo was a friend of Del Monte but had yet to make his mark on cosmology.

The Villa Aurora is private property in the hands of the Ludovisi family and can be visited upon request, but only in groups, with a charge of $300.

Odescalchi Balbi private collection - Palazzo Odescalchi, Piazza del Sainti Aposto ![]()

27. Conversion of Saint Paul 1600

This is one of at least two paintings by Caravaggio of the same subject, the Conversion of Paul. Another is The 'Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus', in the Cerasi Chapel of Santa Maria del Popolo. [No. 22 in this list.]

The painting, together with a 'Crucifixion of Saint Peter', was commissioned by Monsignor (later Cardinal) Tiberio Cerasi, Treasurer-General to Pope Clement VIII, in September 1600. According to Caravaggio's early biographer Giovanni Baglione, both paintings were rejected by Cerasi, and replaced by the second versions which hang in the chapel today. The dates of completion and rejection are determined from the death of Cerasi in May 1601. Baglione states that the first versions of both paintings were taken by Cardinal Giacomo Sannessio, but another early writer, Giulio Mancini, says that Sannessio's paintings were copies. Nevertheless, most scholars are satisfied that this is the first version of The Conversion of Paul.

The painting records the moment when Saul of Tarsus, on his way to Damascus to annihilate the Christian community there, is struck blind by a brilliant light and hears the voice of Christ saying, "Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?...And they that were with me saw indeed the light, and were afraid, but they heard not the voice..." (Acts 22:6-11). Elsewhere Paul claims to have seen Christ during the vision, and it is on this basis that he grounds his claim be recognised as an Apostle: "Have I not seen Jesus Christ our Lord?" (I Corinthians 9:1).

Caravaggio biographer Helen Langdon describes the style of Conversion as "an odd blend of Raphael and clumsy rustic realism," but notes how the composition, with its jagged shapes and irrational light which licks out details for their dramatic impact, creates "a sense of crisis and dislocation [in which] Christ disrupts the mundane world."

Several modern commentators have questioned whether the rejection of the first versions of Caravaggio's two paintings was quite so straightforward as the record makes it seem, and speculate that Cardinal Sannessio may have seized the opportunity of Cerasi's unexpected death on 3 May 1601 to, in effect, seize the paintings. Certainly there is no obvious reason for the rejection, and the two second versions which replaced them were, if the surviving first version of The Conversion is a guide, (the first Crucifixion of Peter has disappeared), far more unconventional than the first.

Private Collection of the Prince Borghese ![]()

28. Portrait of Pope Paul V 1605

(attribution to Carivaggio disputed).

Camillo Borghese reigned as Pope Paul V from 1605 to 1621. Caravaggio's biographer Giovanni Bellori records that the artist painted a seated portrait of him as pope, which must place the work between Borghese's election on 16 May 1605 and Caravaggio's flight from Rome in May 1606 following the death of Ranuccio Tommassoni. The portrait is attested in the Borghese collection from 1650.

Camillo Borghese reigned as Pope Paul V from 1605 to 1621. Caravaggio's biographer Giovanni Bellori records that the artist painted a seated portrait of him as pope, which must place the work between Borghese's election on 16 May 1605 and Caravaggio's flight from Rome in May 1606 following the death of Ranuccio Tommassoni. The portrait is attested in the Borghese collection from 1650.

Many scholars have doubted the authenticity of this painting, considering the composition too uninspired for the artist's style. But the scholar John Gash in his authoritative (revised) 2003 catalogue of Caravaggio believes the work is genuine, pointing out that the pose would have been beyond the artist's control - Paul V was noted for his dignified and even taciturn demeanor, and would be unlikely to accept direction. "[H]is unostentatious bearing exemplifies the sober, cautious and, in fact, genuinely religious spirit of the man...". Gash also points out that Paul's narrowed eyes, far from conveying suspicion and malevolence as many writers assert, are the result of chronic myopia. Also note the startling similarities between this portrait and Velázquez's 'Portrait of Pope Innocent X'.

According to Bellori, Caravaggio obtained his introduction to Paul through the papal nephew, cardinal Scipione Borghese. Scipione was an avid art collector, destined to acquire many of Caravaggio's canvasses, but he was to prove of little value as a patron either to Caravaggio or to others, preferring to enhance his collection through extortion and sharp practice rather than by support and purchase. He would eventually become one of the crucial figures in Caravaggio's final days.

29. Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy 1606

Caravaggio's 'Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy' (or variations on that name) exists in at least eighteen copies, of which this version, in a private collection, has been claimed as the most likely original.

Caravaggio's 'Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy' (or variations on that name) exists in at least eighteen copies, of which this version, in a private collection, has been claimed as the most likely original.

According to a legend popular in Caravaggio's time, after Christ's death his faithful female disciple Mary of Magdala moved to southern France, where she lived as a hermit in a cave at Sainte-Baume near Aix-en-Provence. There she was transported seven times a day by angels into the presence of God, "where she heard, with her bodily ears, the delightful harmonies of the celestial choirs."

Earlier artists had depicted Mary ascending into the divine presence through multicoloured clouds accompanied by angels; Caravaggio made the supernatural an entirely interior experience, with the Magdalen alone against a featureless dark background, caught in a ray of intense light, her head lolling back and eyes stained with tears. This revolutionary naturalistic interpretation of the legend also allowed him to capture the ambiguous parallel between mystical and erotic love, in Mary's semi-reclining posture and bared shoulder.